Virtual Memory, Segments, Paging and Big Pages

Virtual Memory via Segments

The idea with segmentation is that the memory of a process is divided into some number of continuous segments. Each segment has a mapping from the address in the process, the virtual address, to the address in physical memory. The segments can be whatever size the program need them to be.

A virtual address might look like this:

[ 4 bits for the segment number| 28 bits for the segment offset ]In such a schema there are up to 2⁴ segments with size up to 2²⁸. That is each segment can be at most 256M. I picked these numbers at random. For this article I will use 32-bit virtual addresses and 64-bit physical addresses just so it’s clear which is which.

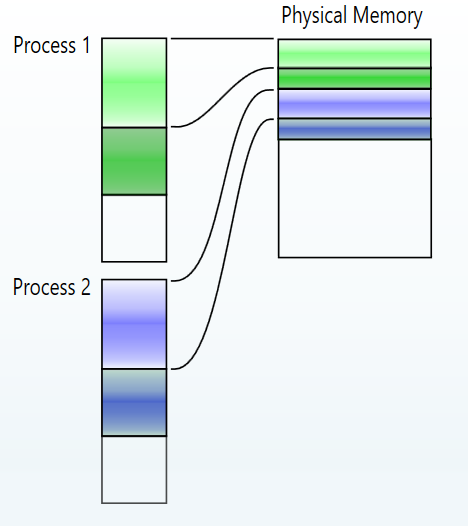

So, we might end up with a picture that looks like this:

As you can see, I squeezed the physical memory to kind of show that there’s a lot of it. The blank areas represent unused memory. The colored areas could slide around anywhere in the physical memory.

Now here’s the thing, to understate the situation, segmented virtual memory is not that popular. Why? Well, lots of reasons.

- The segments could be big and so swapping one out could be mightily expensive. A 256M swap!

- The segments are capped in size so if your program needs an allocation bigger than a segment then life sucks. Famously the 8086 and 80286 processors used 64k segments, which was all kinds of yuck.

- The segments are variable sized, so the physical address space fragments. The OS can only defragment with expensive relocations of potentially huge areas of memory.

Let’s talk about some of the other things that go wrong here:

- If a process wants to grow one of its segments there might not be room in physical memory to accommodate that, so again the OS has to slide memory around.

- If many processes are running the OS might have to stop LOTS of processes to do the necessary slide, ouch!

- Likewise, if a process gives back memory, there’s no easy way to get it back into use because it might give back a strange size. Physical memory will fragment just like with malloc/realloc/free.

- All the other usual malloc problems are present, internal and external fragmentation, etc.

Because of these weaknesses, in modern systems, Segments are only used as logical constructs by loaders and linkers to arrange for related data to be in the same chunk of physical memory and not as an address mapping technique. Sometimes they are equivalently called Sections.

Virtual Memory via Paging

After going over segments, I was introduced to paging which basically exists to get around the problems above. The virtual mapping diagram is substantially the same as before except now the virtual address is divided into equal-sized smaller units. So, of course, there are more of them, and this will be important. A system with paging might look like this:

[ 20-bit page number | 12-bit page offset ]So here there are up to 2²⁰ pages (about a million) each 2¹² bytes big (4k). Creating 2³²B of addressable memory (i.e., 4GB).

INFO

Note: actual page table entries for modern processors are much more complicated than this simplification.

This kind of choice is now the standard way things are done. So, why is this better?

- The operating system only offers one size of allocation, the page size (4k here), no fragmentation ever.

- The OS can page-out and page-in a much smaller unit (4k) to do its virtualization, this is a much more reasonable amount of i/o. Note in such system it’s usually called paging rather than swapping and the backing storage for is often called a page file for the same reason.

- The OS never has to relocate physical memory.

- Management of the backing storage is simpler. It also grows in 4k chunks, the OS can grow it as needed in multiples of 4k and any 4k section of the file can be used by any page.

- Other parts of the operating system that are trying to use memory, like the disk cache, can reasonably get and release memory without causing undue problems in regular allocation patterns.

- Note: I didn’t make a diagram for this setup because literally any page could be anywhere in physical memory. So you can draw any arrows you like. I didn’t see the point.

This comes at a price though. Segments were big and so we only had to manage a small number of them. Pages are small by comparison and so there are more. Many more. In this example up to a million pages. These pages can be stored anywhere in physical memory and so the OS might need up to a million entries mapping each page to its physical address.

Each such entry looks something like this:

[ 52-bit base address | 12-bits assumed to be zero, unstored]And, of course, that’s up to a million entries for each process! There is no way that we can store this much information in the registers of some MMU. The processor has to use some of its main memory for this. This storage is often what we call the Page Table.

Modern Page Tables are complicated beasts because we want them to be dense, but we also want them to allow for lots of gaps in the mapped addresses. I won’t get into all of that here, suffice to say there is a multi-level groups-of-pages style thing going on to get the final base address.

In a 1TB system (2⁴⁰ bytes), I would need 2²⁸ page table entries (that’s about 256 million of them) to map the whole of memory. If the entries were 8 bytes a pop, that’s 2³¹ bytes or 2GB. And that only maps the pages once!

In a running system, the OS might need more page table entries than the above because several processes have them mapped in different ways. Even the fact that the memory is paged-out has to be represented. And, of course, the disk cache also needs mappings…

That’s a lot of mappings.

With the page mappings being in regular memory, you’re in a bad place. No reasonable system could exist that had to do many reads of normal memory in order to do the address mapping so that it can do one real read or write from that very same memory.

The Translation Lookaside Buffer

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) is another cache inside the processor. Like the normal memory cache, the TLB is often segmented into a cache for instruction (code) mapping (the ITLB) and another cache for data mapping (the DTLB). It doesn’t have to be but that’s pretty common. And like the normal memory cache, getting a lot of TLB misses is painful.

The TLB holds the physical address of a bunch of pages that were recently mapped. If your code uses the same page many times (common), or other recently used pages, the processor won’t have to consult the page table again. If it does… well, the page table is itself memory and that too can be cached so maybe it will get the page table quickly. Or maybe it won’t. It might need to pay for several reads if the TLB cache misses. Each read might be something like 50ns — so a bad TLB miss might cost… 150ns? Assuming no paging?

That’s bad.

A modern processor might retire something like (roughly) 1000 instructions in that amount of time. So, yeah, real bad.

What would contribute to having a lot of TLB misses?

- Your process uses a lot of memory (data or code) and hence needs lots of page table entries, more than the TLB can hold.

- Your process uses the memory in random ways rather than some orderly fashion (i.e., your access patterns have bad locality).

- Other processes on the same system are doing the above, ruining things for others (bad actors are why we can’t have nice things).

Note that a TLB might be 1 or 2 kilobytes in size. Enough to hold maybe 256 entries or so. That’s not a lot of entries.

2M Pages in Various Systems

Let’s harken back to the original discussion when we talked about virtual memory with Segments. A lot of those issues start to kind of apply again:

- 2M segments are more expensive to swap.

- A process creating lots of 2M pages might adversely affect memory for other processes so probably additional authority should be required to do so.

- Physical memory gets fragmented and allocating 2M of contiguous memory for a 2M page might be hard. You might not be able to get the memory promptly when needed (assuming hybrid page sizes).

- To work with 2M pages consistently, you might need to relocate other pages, incurring swapping costs in processes other than the one that is paging (again assuming hybrid page sizes).

- You might get a lot of the benefits of 2M pages by automatically consolidating page table entries whenever consecutive pages are found thereby increasing TLB efficacy.

- One big benefit to bigger pages is fewer page faults on initial use, but an OS could automatically load a consolidated page table entry on a big allocation and pre-load without faults (maybe with a hint) even if the underlying memory was not guaranteed to stay as a 2M page. I happen to like this plan.

- A system with just a few different page sizes is not nearly as bad as general sized segments, but you can see that it is already starting to have the same considerations. Uniform bigger pages (e.g. all 2M) has its own considerations which I will likely write about in another article.

Summary and Conclusion

It seems that different operating systems out there are at different stages of evolution on this front. But one thing was clear to me from the twitter discussion. Allocating a big chunk of memory is getting increasingly normal and ordinary boring page management leaves a lot of perf on the table right now. Everyone can agree that faster allocations from the operating system are a good thing. And everyone can agree that fewer TLB entries is a win for everyone. And it seems to me that doing this for code is even harder than doing it for data. Code locality has been a hard problem even from the days when all you could do tune segments in your overlay manager.